Opening: The Name and the Narrative

The November rain of the Pacific Northwest fell relentlessly, washing Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM) in a cold, gray monochrome. Inside the reinforced concrete Operations Center, monitor screens cast a ghostly glow, and the radio crackle of call signs and grid coordinates tore through the taut air. This was where wars were shaped before the first round was ever fired.

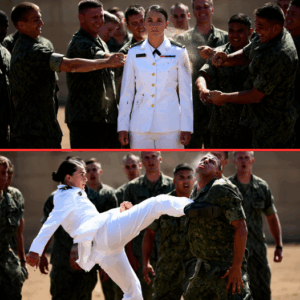

Commander Sierra Vance, 32, US Navy, stood rigid in the hallway outside Briefing Room 3. The service khaki blouse still held the faint, cold dampness of the drizzle. Her name tape read: VANCE. A name as heavy as lead—heavy enough to automatically open one door and slam shut every mind on the base.

She moved sparingly, but when she did, it was with the chilling precision of an assassin. She shifted the tablet under her arm, her fingers steady. Her steel-gray eyes swept the corridor, analyzing every movement, every exit, every threat vector, not out of fear, but muscle memory. There was no performance in Vance’s bearing—just quiet, competence coiled tight as a steel cable.

Forty feet away, Colonel Alistair Cole—a grizzled Special Forces officer with three decades in the shadows—reviewed a logistics manifest. Cole had the ability to read competence the way other men read faces. The stillness of the Naval officer, the way she seemed to hear conversations that hadn’t started yet, reminded him of the intelligence officers who had kept his teams alive in Ramadi and Kandahar.

Chapter 1: The Public Insult

Commander Vance had been here for three days, and Captain Felix Thorne had been talking continuously for three days. Thorne spoke with that particular blend of arrogance and insecurity common in men who are competent but have never tasted excellence.

He was a Ranger-qualified Logistics Captain, two deployments to Afghanistan, and absolutely convinced that naval officers had no business near Army operational planning. When Vance’s name appeared on the observer roster for his joint planning cell, he took it as a personal insult.

And now, he stood blocking the doorway, physically barring her path.

“You only got this assignment,” Captain Thorne said, his voice deliberately loud and sharp so every officer in the operations center could hear the accusation. He folded his arms across his body armor, forming a human wall of steel.

“You got this assignment because your father knew the right people.”

The Army captains and majors hunched over their workstations nodded, some smirking, some pretending they weren’t listening. To them, the 32-year-old Navy officer with the famous last name was just another legacy hire skating by on connections instead of merit.

None of them knew that the woman standing in front of Thorne held a temporary operational appointment as a Captain, signed by the Commander, U.S. Special Operations Command himself, with delegated authority to dismantle their entire command if she found it operationally incompetent. The orders folded in the inside pocket of her service khaki blouse carried the power to end careers with a single report.

“We’re in a critical briefing, Commander,” Thorne said, his arrogance thick. “I suggest you return to an office where you can focus on the numbers.”

Thorne brought a rough hand down on her shoulder, using his strength to shove her aside to clear his path into the room.

The moment his hand settled on Vance’s shoulder, one truth crystallized with perfect clarity:

Some men only learn respect when the person they underestimated destroys everything they’ve built.

Chapter 2: The Weight of Legacy

Sierra Vance grew up at Fort Bragg, in a house where excellence wasn’t praised—it was the minimum passing grade. Her father, Lieutenant General Thomas Vance, had commanded special operations forces, earned multiple high honors, and died in a Black Hawk training accident when she was sixteen.

Before he died, he made sure his daughter understood that legacy is earned in blood and sweat, never inherited. He taught her that standards exist for a reason, and exceeding them was the only acceptable goal.

The Naval Academy was her rebellion—choosing a service where the Vance name carried less weight. She graduated in the top five percent, selected Intelligence, and never looked back.

Eighteen months at the NSA. Joint task force fusion cells coordinating between SOCOM, the CIA, and the DIA. Lieutenant Commander at 29, Commander at 31—promotions earned in classified operations that would never see daylight.

Yemen had been the crucible. Real-time analysis from Djibouti as a Delta strike package closed on a high-value target compound. Thirty seconds before weapons release, fresh sensor data showed not combatants but a wedding—forty-plus civilians. Sierra spotted the discrepancy, built the case, and recommended abort. The mission commander pulled the plug. Dozens of lives saved. An international incident averted. Protocols rewritten.

The cost was isolation. Officers who had wanted the strike didn’t forget who stopped it. Whispers followed her: protected because of her father, too cautious when hard calls were required.

Six weeks ago, USSOCOM gave her temporary Captain’s rank and orders that turned whispers into weapons. She was tasked to assess joint readiness at select installations under administrative cover—meaning her real authority stayed hidden until she decided otherwise.

Three days at Lewis-McChord had been enough.

Chapter 3: Authority Revealed

Thorne had spent three days undermining her authority.

Now he stood smug in the doorway, certain he had won.

Sierra felt the weight of fifteen years of assumptions pressing down—not the clumsy shove, but the cumulative burden of every person who saw the name tape and decided they already knew her story.

She could have ended this on day one. One conversation with Cole, one flash of the orders, and the entire ops center would have snapped to attention. But that would have enforced compliance through rank, not fixed the disease.

Her father’s voice, echoing from fifteen years ago, standing in the pine forest at dawn: “You’ll spend your career proving yourself to people who’ve already decided you don’t belong. Let that make you angry and it will eat you alive. Let it make you excellent and it compounds.”

She had chosen excellence.

Sierra reached into her pocket, withdrew the folded orders, and handed them—not to Thorne—but to Colonel Alistair Cole, who had been watching the entire exchange from his desk.

Cole’s eyes flicked across the letterhead, the signature, the authorities granted. He read it twice. When he looked up, the temperature in the corridor seemed to drop ten degrees.

“Commander Vance. Captain Thorne. My office. Now.”

The shift in tone was absolute.

Thorne followed, confused but still puffed with residual triumph.

Cole closed the door.

“Captain Thorne,” he said, his voice winter-cold, “explain to me why you just physically prevented a senior officer from entering a briefing she was authorized to attend.”

Thorne straightened. “Sir, Commander Vance has been disruptive—”

“You made a judgment call about an officer senior to you.” Cole cut him off, placing the orders on the desk. “Read.”

Thorne leaned in. The color drained from his face in stages—confusion, recognition, horror.

The document identified Captain (temporary) Sierra M. Vance, USN, as USSOCOM’s designated operational readiness assessor with binding authority to observe, direct retraining, place personnel on administrative hold, and recommend relief for cause. A separate paragraph authorized her to operate under cover to prevent distortion of normal behavior.

When Thorne looked up, his mouth worked soundlessly.

“You have spent three days,” Cole continued, “undermining a senior officer conducting an authorized inspection of this command. You created a hostile work environment. You spread demonstrably false narratives about her qualifications. And thirty minutes ago you committed hands-on interference with her duties. Do you comprehend the magnitude of what you’ve done?”

“Sir, I didn’t—”

“The personnel file showed exactly what it was meant to show,” Cole snapped. “Any officer with a functioning brain would have asked why a 32-year-old Navy commander had access to spaces that require flags and stars to enter. Instead you decided—based on her age, her gender, and her last name—that she didn’t belong.”

He turned to Sierra. “Captain Vance, your findings?”

Sierra opened her tablet. Her voice was calm, clinical, lethal.

“Seventeen doctrinal violations. Deployment timelines thirty-eight percent slower than standard. Intelligence integration effectively nonexistent. Planning culture rewards ego protection over mission effectiveness. Professional dissent is treated as disloyalty. Captain Thorne is competent in logistics but lacks the judgment required for joint coordination. His behavior is symptomatic of systemic failure.”

Cole absorbed it like a man receiving a terminal diagnosis he already suspected.

“Recommendations?”

“Immediate restructuring of planning procedures. Mandatory joint doctrine retraining for all officers. Formal counseling for personnel who participated in the hostile environment. Captain Thorne is to be removed from any position requiring joint coordination or personnel supervision.”

Thorne looked as if the floor had vanished beneath him.

Cole didn’t hesitate. “Captain Thorne, you are relieved effective immediately. Report to my aide for administrative restriction orders. Your career in joint operations is over.”

He turned back to Sierra, something close to awe in his eyes. “Captain Vance, I failed to intervene earlier. That failure is mine. What do you need from me now?”

“An all-hands formation in two hours. You will announce the procedural changes as USSOCOM-directed requirements. Captain Thorne will attend and will publicly acknowledge his actions and their consequences. The rest of the staff will receive private counseling as required. Public humiliation is unnecessary; correction is.”

Cole nodded, respect plain. “Understood.”

Sierra looked at Thorne one last time.

“You are a competent logistics officer, Captain. If you learn from this—if you understand that competence comes in forms you don’t recognize and that your assumptions cost the military talent it cannot afford to lose—then something may yet be salvaged. But remember this moment the next time you decide someone doesn’t belong because of who their father was or what they look like. You may be dismissing the one person standing between your soldiers and their graves.”

Thorne couldn’t meet her eyes.

Three weeks later he was gone—reassigned to a supply depot in central Texas, career effectively finished.

Major Torres and Captain Kim received written counseling and mandatory retraining. Colonel Cole executed every recommendation. Four months later, during a no-notice USSOCOM readiness exercise, the JBLM joint operations cell scored in the top tier.

Sierra Vance completed her tour and returned to MacDill. Her Lewis-McChord report became required reading for every O-5 and above in joint billets.

She stood in her office, looking at the photograph on her desk—her father in dress blues, two months before the crash. She touched the thin scar on her left wrist, a souvenir from a night land-navigation course when she was fourteen and he refused to let her quit.

Pain, he had told her, is just information. Not permission to stop.

Somewhere at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, officers were learning that competence matters more than assumptions.

It wasn’t redemption.

It was just progress.

And excellence, as always, was compounding.

News

Two fires, one culprit? The chilling truth behind the blazes that erupted at 2 a.m. in Adelaide

Police are investigating two suspected arson cases in Adelaide overnight, believed to be linked. Events began at 2am today when firefighters and police…

The breathless rescue of the ancient lamp after more than half a century deep underground: Brian O’Brien’s final wish has come true!

Brien O’Brien’s carbide lamp has been retrieved from a cave at Yarrangobilly. (ABC South East NSW: Adriane Reardon) An old-fashioned…

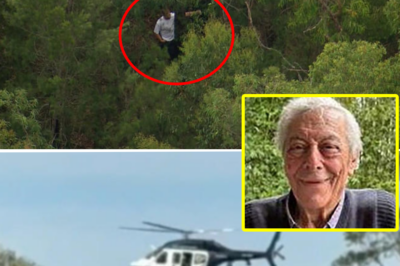

Who was the actual target in the mistaken kidnapping of the 85-year-old man?

Kidnappers who mistakenly abducted an elderly man from his home were believed to be targeting a relative of a Sydney…

Family in panic, police issue search order for 25-year-old man missing from medical facility

Police have issued a public appeal as they search for a 25-year-old man who disappeared from a medical facility in…

Sydney’s mistaken kidnapping nightmare: The real “target” remains safe, while an 85-year-old man languishes in the deep forest awaiting d3:ath!

Police have extracted forensic evidence from a burnt-out car with cloned plates found in north-west Sydney in the search for kidnapped…

“Chris, don’t leave your parents”: Chris Antony’s father’s heart-wrenching cries brought millions to tears

Heartbroken parents have shared their devastation at coming across a crash scene involving their teenage son. Chris Antony died in…

End of content

No more pages to load