Colonel Lewis Lee Millett’s life reads like a ledger of American wars, written across three decades and three continents, with a stubborn line at the bottom that says: stand and fight. Before he was the Medal of Honor recipient who led a bayonet charge up a Korean hillside, he was a Massachusetts teenager impatient with peacetime. He joined the National Guard in 1938 while still in high school, already convinced that war—if it came—would demand commitment, not half measures. When fighting erupted in Europe and President Franklin D. Roosevelt promised that “no American boys” would be sent to fight there, Millett made a brash, controversial choice. He deserted, crossed the border, and enlisted in the Canadian Army. It was a young man’s calculus: if history was calling, he would not wait on politics to answer.

That detour placed him in Britain, where commandos hammered him into the kind of soldier who thrives in chaos: physically tough, inventive, and comfortable with risk. When the United States entered World War II, he walked into the U.S. Embassy in London and rejoined the American Army. North Africa, Sicily, and Italy followed with the 1st Armored Division—hard campaigns that stack up decorations, scars, and a reputation. By the time his old court-martial papers caught up with him, he’d already earned a battlefield commission and proven too useful to sideline. The charges were torn up, a bureaucratic concession to the reality that the war had already judged him: capable and brave when it counted.

After the war, he stepped away from active duty, then returned to it as the world lurched into the Cold War’s first hot conflict. Assigned to the 25th Infantry Division’s 27th Infantry Regiment—the storied “Wolfhounds”—Millett found himself in Korea in 1951 facing a fortified, windswept hill held by Chinese troops. He decided to fight on primitive terms that cut through fog and fear: steel against will. “They said Americans were afraid to use the bayonet,” he later explained, so he had local Korean women grind his men’s blades razor sharp and drilled hand-to-hand techniques until they were muscle memory. Then he ordered the assault—bayonets fixed—and led two platoons uphill through fire.

The charge worked because it was audacious and personal. Bayonets collapse distance; they shove soldiers into the same brutal square yard. Millett was wounded in the melee, but refused evacuation until the position was secured. For that action on February 7, 1951, he received the Medal of Honor. He always minimized the heroics as a reflection of his men more than himself, but the citation captures the essence: leadership shown not from a map table but from the front, translating resolve into momentum.

Millett’s career was a string of firsts and forewarnings. He made five combat jumps, was the first U.S. officer to rappel from a hovering helicopter, and built institutions that taught others to move and think like him. General William Westmoreland—whom Millett considered a fine commander—asked him to turn his raid craft into a school. From that charge came the Army’s Recondo program, a crucible designed to raise the average soldier’s fieldcraft well above the baseline learned in basic training. The premise was simple: most units didn’t patrol as well as they needed to; training had to be sharper, more realistic, more punishing. He started with squad leaders and scaled up.

Vietnam widened his laboratory and hardened his edges. He went in 1960 to stand up Ranger-style training for South Vietnamese and Laotian troops, then returned in 1970 as an adviser in the Central Highlands, moving from Da Lat to Pleiku and Kontum. He patrolled with ARVN Rangers, set ambushes, and fought. He rated his South Vietnamese students highly once trained and never hesitated to join them in the field. On weapons he was a traditionalist by experience: an M1 Garand man to the end, skeptical of the M16’s reliability, and loyal to the .45-caliber pistol over the 9mm. These preferences weren’t nostalgia; they were born of days when a rifle that always fired meant you lived to see the night.

His most controversial tour involved the CIA’s Phoenix Program, which he defended as a hard, necessary tool aimed at dismantling the Viet Cong’s covert infrastructure. Millett’s role, as he described it, revolved around intelligence gathering and ambushes triggered by that intelligence. “No torture,” he insisted—an assertion that collides with the program’s enduring, bitter politics but aligns with how he wanted his service remembered: ruthless in pursuit, disciplined in method. He even volunteered once as a hostage during negotiations for the surrender of an entire North Vietnamese battalion; more than a hundred laid down their weapons, he said, and many later joined the Chieu Hoi program as scouts.

If his résumé is studded with episodes, his worldview is consistent: wars should be entered to be won, and leadership determines everything. He believed the United States should have fully committed in Vietnam while aggressively building ARVN capacity. He lamented the endgame of 1975 as a failure of will and strategy. He also carried a long grievance on behalf of his peers—how Vietnam veterans were treated on return. It wasn’t bitterness for himself so much as an unforgiving ledger entry: the nation asks for sacrifice; it owes, at minimum, respect.

Millett’s sense of service stretched backward and forward through his family. He traced a lineage of Americans who fought from colonial times to the late twentieth century, and he lived to suffer what thousands of military families know: a son lost in 1985 among hundreds of peacekeepers killed in a plane crash in Newfoundland. By the time he retired in 1973, he had done nearly everything the Army could offer a fighting officer. Asked late in life to sum it up, he said he had “a hell of a good time”—a bracing, unsentimental epilogue to a career that measured satisfaction in competence and camaraderie more than in ceremony.

He died on November 14, 2009, at a VA hospital in Loma Linda, California. The final image worth keeping is not only the bayonet charge that made his name, but the teacher behind it—the man who believed ordinary soldiers could be taught extraordinary things, then proved it in classrooms and on ridgelines. In Millett’s ledger, courage is contagious, training is mercy, and history doesn’t wait for permission. It asks whom you will follow uphill—and whether you will fix bayonets when it matters

News

1966 Indochina Battlefield: One Whispered Order That Saved a Marine Unit From Annihilation

Amid the fiery chaos of the Indochina battlefield in 1966, Lieutenant Richard N. Murray — a U.S. Marine hardened by…

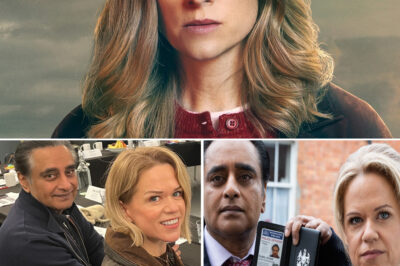

ITV Confirms Major Update on Unforgotten — and After the Flood Fans Will Be Delighted Too

Unforgotten is officially back for a series 7, with fan favourites DI Sunny Khan and DCI Jess James returning to…

Lynley Season 2 Finale Explained: Hidden Clues, Unanswered Questions, and the Future of the Series

Lynley series 1 ending explained and what we know about a series 2 Will DI Thomas Lynley and DS Barbara…

BBC Breakfast’s Carol Kirkwood Opens Up About a Painful Reality in Emotional Confession

BBC Breakfast weather presenter Carol Kirkwood has opened up on her personal life and admitted it’s “sad” when “relationships break…

Australia Day Turns Apocalyptic as 50°C Heatwave and Firestorms Force Families to Flee

State braces for hottest Australia Day in history© Nine Hundreds of people have fled their homes as resurgent bushfires continue to rage in Victoria during…

“I Wish You Were Still Here”: Son’s Heartbreaking Farewell as NSW Triple-Murd3r Investigation Intensifies

The son of one of the victims of an alleged triple-murder in the NSW central west has written an emotional message to…

End of content

No more pages to load