Missy Redding’s son Nikolas was killed in college. She didn’t want to make headlines by medically extracting his sperm for a surrogate pregnancy — she just wanted to keep his dreams alive

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2):format(webp)/Missy-Redding-012126-fe065b62c1324809802c20e60dfef566.jpg) Missy Redding with her son Nikolas Evans and Evans as a boy (right).Credit : Missy Redding

Missy Redding with her son Nikolas Evans and Evans as a boy (right).Credit : Missy Redding

Nikolas Evans was in middle school when he set a goal for himself quite unlike a lot of other children his age: to become a father one day.

“He was going to have three boys. He want[ed] me to have a lot of grandsons,” his mother, Missy Redding, tells PEOPLE. “He already had his names picked out.”

And his mom believes he would have had those kids, too — an entire bustling family — if a freak incident hadn’t cut his life short.

Evans was living in Austin, Texas, to attend film school when, on March 27, 2009, the 21-year-old whom everyone called Nik was critically injured when he was punched while breaking up a fight outside a bar, according to Redding.

“One of the blows hit him at the side of his head and immediately knocked him out, and he hit his head on a curb,” she says.

His killer, Eric Skeeter, remained at large for months. After agreeing to a deal with prosecutors, Skeeter pleaded guilty to manslaughter in 2010 and was sentenced to 10 years of community supervision.

Court documents state that Evans was punched once in the face before he hit the ground and fell unconscious. His mom believes his suffering may have been worse.

“They call it a ‘one-punch homicide,’ “ Redding says. “It’s annoying, because the autopsy could not confirm that it was one or six or 42.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2):format(webp)/Missy-Redding-111725-275daa417b7b48c0a41d6827cde879f2.jpg)

From left: Missy Redding with her sons, Nikolas and Ryan Evans.Missy Redding

Evans lived, initially. He was taken to the University Medical Center Brackenridge where he was placed in the intensive care unit and in a medically induced coma. His mom says he had two surgeries to relieve pressure and bleeding in his brain.

At one point, she says, he “woke up to tell me that he loved me.” Then he died on April 5. According to his autopsy, the cause was blunt force trauma to the head.

This is where the story of Evans’ death gets more complicated: Redding agreed to allow her son’s organs to be donated. But she had another idea, too.

She decided to have some of his sperm extracted as part of what’s known as postmortem or posthumous sperm retrieval, or PSR, which allows the loved ones of deceased men to use their DNA to try and have their biological children through other means — in Redding’s case, through a surrogate embryo.

“Okay,” she remembers thinking. “I’m just going to create another Nikolas.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2):format(webp)/Missy-Redding-111725-3-cc8cd86a5e1d443c98f121ee1732f667.jpg)

Nikolas Evans as a baby.Missy Redding

The first documented case of PSR was reported in 1980 and the first baby born as a result was in 1999, according to Health. The U.S. has “no government regulations for when and how PSR can be performed,” and “the decision is up to individual hospitals and fertility clinics,” the outlet notes.

The procedure has emerged as the subject of ethical debate among medical experts, including over the thorny issue of consent.

Redding’s choice sparked national headlines and even mockery as “the crazy sperm lady,” she says.

Looking back, Redding, now 59, tells PEOPLE that she was grieving — despairing — and looking for a way to somehow “recreate” Evans amid the monthslong search for the man that attacked him.

Years later, she easily remembers her “Nikki,” the boy and teenager he’d been and the young man he was becoming.

“He was just a really good-natured, good guy. Super smart, not altogether athletic,” Redding says. “He did find his niche in junior high. He tried a whole bunch of things as a kid and little kid, but he was just kind of a duck out of water until he started long-distance running.”

“Sometimes he’d run 15 or 20 miles, and I think that was his peace place, and where he found a lot of his Zen,” she adds.

Redding, a master esthetician from Rockwall who has an older son, Ryan, with her first husband, wasn’t intending to wade into provocative territory when she decided to move forward with the procedure.

She wanted what seemed, to her, like something much simpler as a parent: to give her son some kind of future; to help his dreams come true.

“I couldn’t help him graduate from college, I couldn’t help him get married to [his girlfriend] Vicky, I couldn’t help him have a screenwriting career,” she says. “I couldn’t help him with any of that other stuff. But I could help him have grandkids, have kids, because that’s something that was really, really important to him.”

From the start, though, there were problems.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(665x0:667x2):format(webp)/Missy-Redding-111725-5-984dac0a5a044b6e9c9d80e7326b5bc6.jpg)

Nikolas Evans.Missy Redding

The hospital — which has since closed — did not want the procedure to happen, Redding says. So the day after Evans’ death, she hired attorney Mark Mueller and went before a Travis County probate judge.

Mueller, 73, tells PEOPLE that he was doing a screening in Los Angeles for a movie he produced when another lawyer reached out and told him about Redding’s “very unusual” case.

“There was a limited amount of time in which the sperm would remain viable,” he says. “And there was no will. There was no legal precedent for something like this — period.”

From California, Mueller says, he directed his legal team to file a petition with the judge, who ruled in their favor. The Travis County Medical Examiner’s Office was ordered to permit the harvesting of Evans’ sperm and, if needed, to preserve his body in near-freezing temperatures to ”ensure continued viability of the sperm.”

News of Redding’s legal fight made waves in Texas and across the country. With the attention came ridicule and backlash. She says she even attempted suicide.

“After I harvested his sperm and I did the Today show, this Catholic priest used to call me at 5:30 every morning for six months,” she says, “to tell me that I was creating the demon spawn against God.”

“But really, I didn’t care,” says Redding. “I had the support of my family, and especially my husband [Jeff] and my son. And I think [Ryan], at the end of the day, probably was like, ‘Oh, boy, mom.’ But also, I’ve never been a woman who you could tell ‘no’ to. I’m always going to find a way if I want to get something done.”

She says she’s never quite understood all of the negativity: “I get that it’s creating a life, but it’s not creating a life to put a child into a foster care system. It’s creating a life to have a beautiful life.”

The spotlight had its benefits, especially in the early months when her son’s case had not been closed.

“I used that attention to try to find Eric Skeeter,” Redding says. “So I was happy to talk about the sperm as long as they would talk to me and talk to the people about the fact that we did not find my son’s murderer.”

Evans’ extraction was successful. The hard part was finding an egg and a potential surrogate.

Redding says she had two longtime family friends who offered to do it, “then once we would get to doctors or we would be referred to specific people, all of a sudden the cost went from $35,000 to $115,000, or, ‘Oh, it’ll be $125,000.’ “

She considered carrying the donated embryo herself, if the process got to that point.

In part because of the price, and because of the continued media focus, Redding ultimately decided to look outside of the United States.

A stranger helped make it all possible, Redding says: The man who received Evans’ donated heart then gave her the money she needed to continue trying to make an embryo with Evans’ sperm.

“He said, ‘I want to do this. I have the gift of life. I want to do this. I want to help you,’ ” she recalls.

Around the end of 2010, Redding found an egg donor in Europe with a similar racial background as her son’s girlfriend, which she found to be a touching coincidence.

The sperm and egg samples were shipped to doctors all over the continent to try and make an embryo, but “it didn’t work,” Redding says.

By 2013, she was ready to set aside her quest for a grandson through Evans’ posthumous DNA. She hasn’t pursued it for more than a decade.

Still, she has no regrets.

Today, Redding, who changed careers and works as a project manager at a women-owned construction company, has a new goal: She’s been pushing to pass a law in Texas to bring mandatory manslaughter judgments to culprits of the same “one-punch homicides” that killed her boy.

It’s a dream she is optimistic will be fulfilled one day.

“Half of my heart is gone forever,” she says. “There’s no replacing that. But we’ve done a lot of good things over the years, and I’m really not giving up hope on doing this.”

News

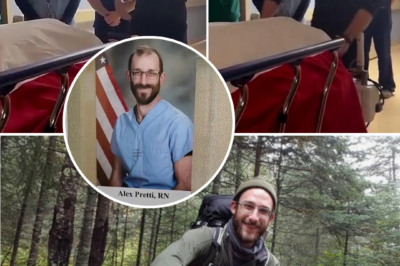

“He Was There For Me When It Mattered Most…” — Air Force Veteran Recalls How Nurse Alex Pretti ‘Comforted’ and ‘Helped’ Him Weeks Before His D3:ath

“I’m saddened to the deepest part of my heart,” veteran Sonny Fouts, 71, tells PEOPLE of Pretti’s death Alex Pretti.Credit…

“‘FREEDOM IS NOT FREE’…” — Nurse Alex Pretti’s Viral ‘Final Salute’ for Veteran Patient Resurfaces After His F4tal Sh0:oting

“Today we remember that freedom is not free. We have to work at it, nurture it, protect it and even…

“Ignore the Noise — Just Press Play” — Netflix Fans Defend ‘Fantastic’ Movie Despite Shockingly Low 9% Rating

A British thriller featuring Daniel Kaluuya, Aaron Taylor-Johnson and Richard Madden is a must-watch on Netflix despite its poor reviews….

“From the Very First Scene, It Pulls You In” — ‘Masterpiece’ Historical Crime Drama Is Already Captivating Netflix Fans

The movie follows an aspiring artist who becomes a master forger for criminal gangs in 1970s Rome. The Italian film…

““It Only Takes One Scene, You Can’t Stop Watching” — The ‘Top 10 Shows of the Last Decade’ Netflix Fans Binge in One Day

Fans have rediscovered the 10-part Netflix series with an impressive Rotten Tomatoes rating Netflix viewers are only now rediscovering a…

“The Moment You Hit Play, There’s No Turning Back” — A Yellowstone Star’s New Thriller Is Leaving Viewers Stunned

Kelly Reilly stars in the new six-part crime drama, which has just premiered its first two episodes on Sky. Yellowstone…

End of content

No more pages to load